I’ll return to StageIt on Saturday, February 26, 2022 at 9 pm EST. Theme: airplanes. Ticket and info: here.

Official Website

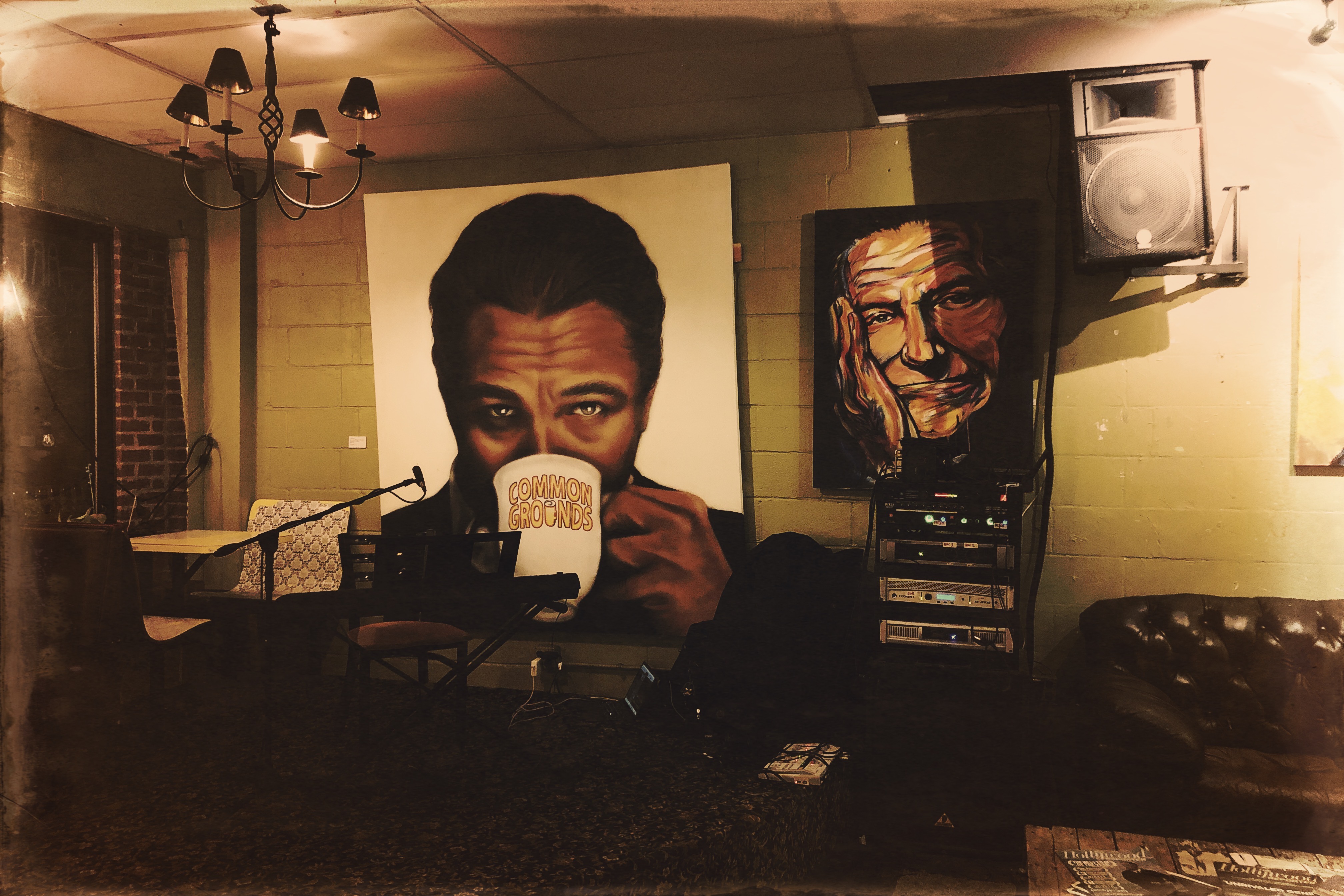

Neither the ice storm nor the pandemic caused my show at Common Grounds to be postponed. On Saturday, January 22, 2022, from 8 pm until about 11 pm, I performed my first all-piano coffeeshop show.

Playing a piano show out live is uncharted territory for me. I’ve played solo piano limitedly, a few times, and I have been trying new gear setups each time. These have consisted of either running straight out through the stereo output of my Yamaha keyboard or using a less than ideal MIDI keyboard to trigger robust samples. This time, however, I tried using my Yamaha keyboard into my MacBook Pro where I triggered a piano in GarageBand. I liked this outcome.

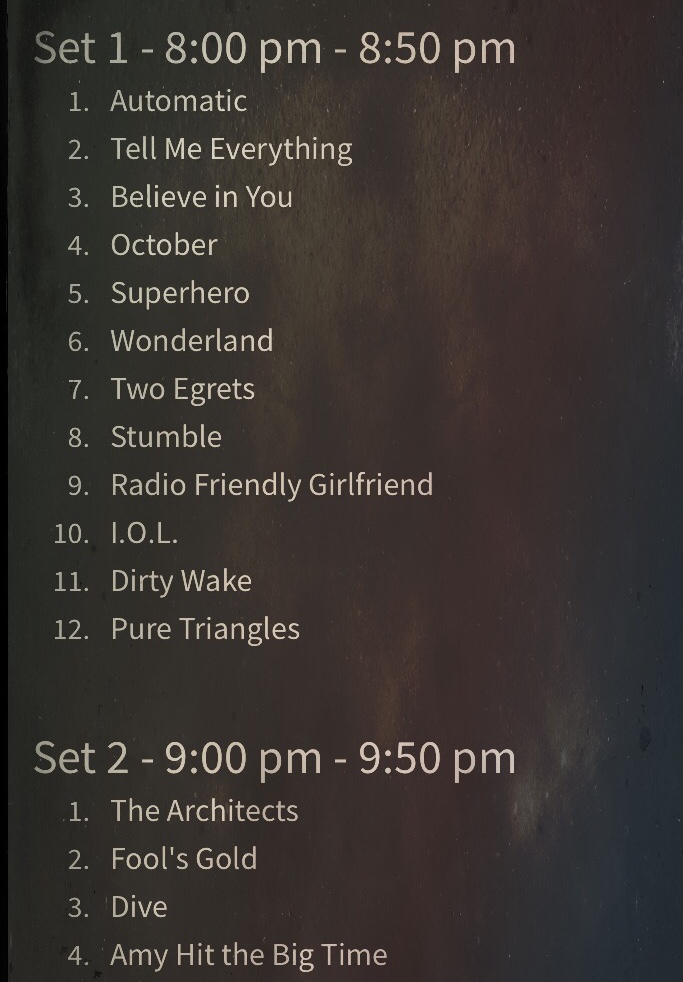

Collapsis played three reunion shows in 2021. As such, Dirty Wake, our principal album, has been on the fore-front of my mind. The first set of the evening was nearly all of Dirty Wake in sequence, with the exception of “I.O.L.” That song is tricky and seldom played. The second set was nearly all of Semigloss Albatross, the exception being “The Wall of Flies.” Rather than take a set break, I went straight into what was going to be the third set, which ended up being a handful of cover songs and balanced with a smattering of originals.

I look forward to doing this again. While my sets were structured, not all of the songs I chose lent themselves easily to the piano. Next time, a better approach would be two 45 to 50 minute sets, with more attention to overall flow and ease of performance.

Over the past year, in between workdays and perhaps while occasionally procrastinating, I’d sometimes surf over to the Slate Digital page and salivate over the ML-1 microphone and its many emulations. The Slate Virtual Microphone System self-describes as a “hybrid system that utilizes an extremely transparent condenser microphone, a sonically-neutral preamp, and state-of-the-art digital processing suite that recreates the tone of classic microphones and preamps.” I’ve always enjoyed the recording sessions where I’ve been able to use a 1073 Neve pre-amp or a Neumann microphone that’s more expensive than my car. But, can an emulation system approach the quality of expensive reality?

I picked up an ML-1 last month because they were on sale. I have been using the Slate Virtual Mix Rack for a number of projects, but I hadn’t yet ventured into using Slate hardware. Lately, my go-to microphone has been the Shure SM-7B. How does the ML-1 compare?

This past week, I tried the ML-1 on three different projects. I’m recording vocals on a new collaboration called “Anchors,” I’m revisiting some older songs on the piano, and I’m prepping this month’s podcast. I was very pleased with the ML-1 on straight singing applications. One of the emulations is the SM-7 and, honestly, I couldn’t tell the difference between the emulation and my own SM-7B. If anything, the ML-1 is constructed differently than the SM-7B and sound arrives at its capsule differently, but that affects the mechanics of things more so than the actual sound. While I liked all of the emulations, I particularly admired the Neumann 67 model on my voice. The top is much clearer than the Neumann TLM 103 I have in my mic locker.

I also tried the ML-1 on spoken word. I didn’t prefer the ML-1 on spoken material. Here is where the broadcast pop filter of the SM-7B comes in handy. I’m sure I could put the huge foam filter over the ML-1, but I didn’t try that. In the ML-1’s defense, I wouldn’t use a tube condenser on spoken word either. I bet the ML-2–the Slate mic designed for “instrument” applications–would produce a more favorable result for spoken word.

Bravo to Slate Digital for creating a wonderful piece of gear. I’m sure audiophiles could nitpick the ML-1 and tell us all why the originals are so much better. But for most of us who have lives, families, and a limited budget, emulation systems like the Slate VMS are a dream come true.

On New Year’s Eve, Jonathan Ferreri and I posted a teaser image for our upcoming co-written single, “Anchors.” The new song arose from the same process that created “Comatose,” our last single. Although the singles are credited under my brand, both arose from the spirit of collaboration.

Our process begins with a musical idea from Jonathan. He arranges a sound bed with guitars, drums, and bass. Often, the idea will contain a hint of melody or perhaps a countermelody for me to develop. We agree on the title of the song by way of a poll–we each come up with five proposed titles and then the title with the most votes wins. Working from a title helps me frame the lyrics around the provided sounds. “Comatose,” for example, invited sleep imagery where “Anchors” suggested a deep ocean scene. I develop a chorus first, trying to place the title within the main hook, and then I write verses and a bridge. The writing process ends with me sending a recording of a rough vocal over the original demo back to Jonathan.

Next, Jonathan builds, revises, and edits the original demo to the point where it’s ready for a final vocal. Often, this involves replacing MIDI drums with live drums. Here, Jonathan enlists the services of Chris Broome, a drummer and engineer who facilitates the transition and recording. Chris will enlist a bass player and Jonathan will re-record some guitars at Chris’s studio. Meanwhile, I’ll be working on recording a final vocal in my studio. Being tasked with vocal production, and only vocal production, has been liberating. When I’m tasked with doing everything, I find myself focusing on the big picture to the point where important minutiae gets overlooked.

Once we have all the parts ready, Jonathan and Chris mix the song at Chris’s studio. Although I am not present for the mix, I am in the loop and approve the final. With “Comatose,” there was just one blemish that I requested a polish on and volume ride in a section. With “Anchors,” I anticipate a similar process. After we have the final mix, we send the track to Joe Bozzi in Los Angeles for mastering.

Collaboration produces less revisions because more ears are working on the project. It’s probably the same number of personnel hours, but those hours are divided by the number of people working on the project. The end result is more efficient and more balanced, reflecting the views and tastes of several people rather than one, myopic view.

I’m happy to announce that I’ll be playing a solo piano set at Common Grounds, one of my favorite Greensboro, NC venues. Please join me on Saturday, January 22, 2022 at 8 pm for three sets of original music.

Common Grounds is located at 602 S Elam Ave, Greensboro, NC 27403. Click here for more information.

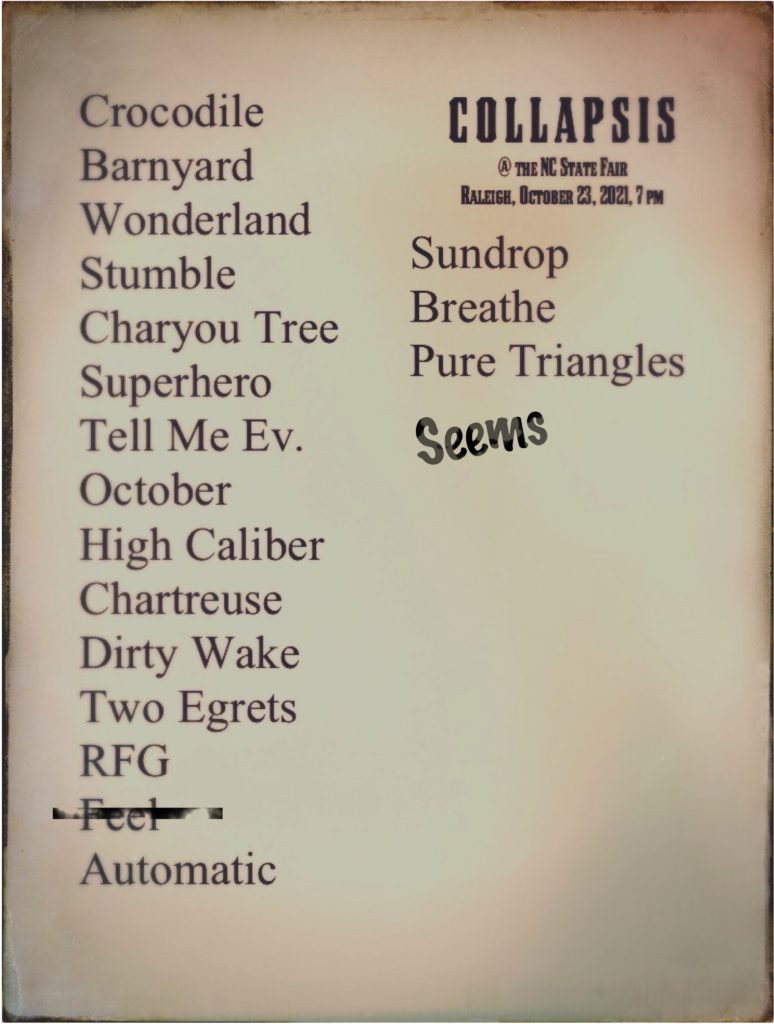

As we played our set on the Waterfall Stage at the NC State Fair, I thought about time travel. Between songs, I announced, “We’re Collapsis, a band from the year 1998. We’ve traveled here to the future to play for you.” To me, the essence of that statement is true. There, at 7 pm, on October 23, 2021, a band that was moderately popular some three decades prior reunited to play the same songs it played long ago. A synergy from the past traveled through some kind of conceptual wormhole only to appear years in the future through the vessels that created it.

Having played the NC State Fair twice now, I can confirm that the greatest obstacle a band faces when playing anywhere near the fairgrounds when the fair is in full swing is getting to the stage. We attempted to caravan to the stage after meeting up at Sushi Nine, only to fail in that simple one mile distance. Our caravan fell to pieces, first because of the size of one of our vehicles and second because of poor pedestrian management near the vendor admission gates. Note to future self (and any musician reading this): arrive on the fairgrounds in one vehicle and allow and extra two hours for transit.

Once we got to the stage, the production and production management was world class. Crisp clear monitors and an exciting stage made for an excellent show all around. Special thanks to Deep South Entertainment for doing such an excellent job with the Waterfall Music Stage.

We only omitted the Big Star cover from our planned set. We substituted “Seems” by QSS at the very end.

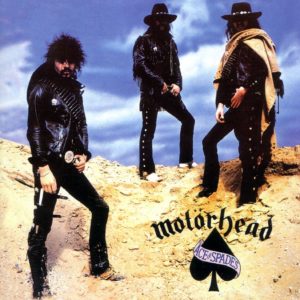

When I was seven years old, I saw the video for Motorhead’s “Ace of Spades” on MTV. I was into metal, but Def Leppard was about as heavy as I got at that age. Something about the “Ace of Spades” video bothered me; as I look at it now, Lemmy’s vocal microphone was at a 45 degree angle downward, rather than the traditional 45 degree angle upward. Knowing nothing about Motorhead or live sound at the time, this was an odd prejudice. As far as I can tell, one reason Lemmy’s mic is pointed downward is because the band’s stage volume was so loud that anything else would result in massive feedback. Although, in later interviews, Lemmy stated that he just liked it that way because he’d have to look at the audience less. While I had heard many individual Motorhead songs over the years, I never gave Ace of Spades a spin in its entirety until recently.

Produced by Vic Maile and released on November 8, 1980, Ace of Spades reached gold certification in the UK soon after its release. The album contains the successful and recognizable single “Ace of Spades” as well as a tour-de-force of relentless, anthemic, big, loud, rock songs.

As for their sound, Motorhead defies specificity. They likely were the loudest band around in the late 70s/early 80s. Their songs are fast and heavy, but not dark, gothic, or political. Lemmy is a powerful singer, but not operatic like his contemporary British metal frontmen (see Rob Halford or Bruce Dickinson). The guitars are distorted and crunchy, but the solos never take on a virtuosic spotlight.

What I like most about Ace of Spades is it’s straight-ahead approach to rock’n’roll. It doesn’t take itself too seriously, but it doesn’t compromise either. Adrenaline sounds like Ace of Spades and vice-versa. Motorhead enthusiasts often recommend Ace of Spades as a fine introduction to the band. The performances are well produced and accessible, while never straying from what makes Motorhead one of the most awesome bands in history.