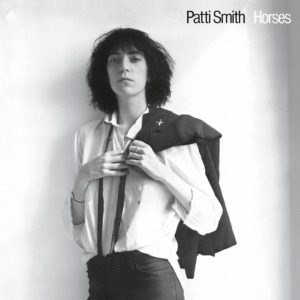

Back when Kickball was first rehearsing, we held our practice sessions in John Gillespie’s hut. The Hut (as it was called) was a 100 square foot building behind John’s mom’s house off of Estes Drive on the north side of Chapel Hill. We fit a drum set, two amps, and three people in the Hut, but not much more. On the wall, John had this awesome poster from a show at Memorial Hall: Patti Smith, Queen of Rock. I had made a mental note to check out Smith’s work. I had heard a handful of her songs scattered here and there through the years, but it wasn’t until recently that I gave her 1975 debut, Horses, my undivided attention.

Produced by John Cale (as in John Cale from the Velvet Underground John Cale) and released on November 10, 1975, Horses has been preserved in the National Recording Registry for being culturally, historically and/or aesthetically significant. In spite of being a critic’s darling of an album and appearing on any reputable “Greatest Albums of All Time List,” Horses has sold less than 500,000 copies. Like the debut album from the Velvet Underground, Horses influenced everyone who heard it, whether or not they actually purchased a copy.

Horses has two outstanding features. First, Smith’s lyrics and phrasing are simultaneously poetic and punk. Fluid, dark imagery runs through Horses veins while Smith delivers her lines with an oddly sincere flippancy. Second, Smith somehow resuscitates new life into garage band classics like “Gloria” and “Land of 1,000 Dances” by reinterpreting them and mashing them together with her own imagery and lyrics. The tension in the opening track is remarkable and when she delivers the “G-L-O-R-I-A,” it’s so satisfying.

Other moments, like “Redondo Beach” and “Break It Up,” evoke different styles than what I expected from Patti Smith. “Redondo Beach” has a reggae flavor while “Break It Up” seems to come from a broken doo wop idea. Both tunes are brilliant.

Patti Smith would go on to release ten more albums since Horses was released in 1975. She would have a commercial breakthrough with “Because the Night,” co-written with Bruce Springsteen, as well as a mid-90s creative resurgence with the albums Peace and Noise and Gone Again. But it’s Horses that gets the prize for innovation, relevance, and being culturally significant.

A