Not far beneath the random silliness of We’re Only in It for the Money, there’s a salient message. As Frank Zappa & the Mothers of Invention perform their rather zany depictions of 60‘s counterculture, song by song, the sum amounts to a scathing rebuke of the Hippie movement. For Zappa, Hippiedom is complete sham—a tool for advancing self-interest that’s disguised by false community, faux spirituality, and lots and lots of drugs. We’re Only in It for the Money does more within its dense 39 minute romp than most artists accomplish in an entire career. It’s a reminder that Frank Zappa is a genre in and of himself and, in 1968, he made a remarkable album.

Released on March 4, 1968 and produced by Frank Zappa, We’re Only in It for the Money peaked at number 30 on the Billboard 200 album chart. While the album sold a fraction of what Beggar’s Banquet by the Rolling Stones or the White Album by the Beatles sold, We’re Only in It for the Money dazzled critics with its razor sharp wit and insane production conventions. The album opens with an audio pastiche of Zappa’s whispers, variety of sounds, and the repeated phrase “Are you hung up?” Then, the record weaves in and out of several one to three minute songs before winding up to the six minute plus noise suite “The Chrome Plated Megaphone of Destiny.”

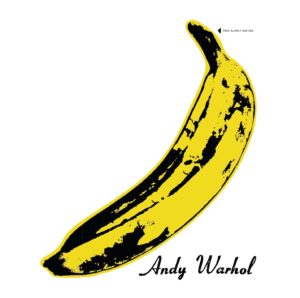

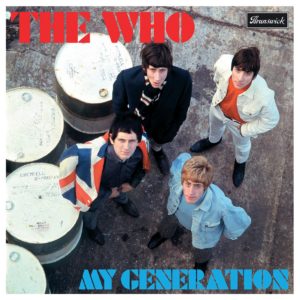

Controversy is Zappa’s center of gravity. The intended album cover for We’re Only in It for the Money parodied Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in an uncomfortable way. If you hold the Pepper and Money covers side by side (and squint your eyes), you might think the covers are the same. A closer inspection shows Zappa’s subversion of and irreverence for the Beatles. Rather than being dressed in marching band uniforms, the Mothers of Invention are dressed in drag. Like Sgt. Pepper, the big bass drum in the center of the album cover has the title of the album, but here, it implies that the Beatles and their late 60s triptik through the counterculture were “only in it for the money.” Oddly, Jimi Hendrix is actually in the photo, but he is surrounded by so many cardboard cutouts that he looks like a cutout. The record label relegated the intended cover to the inside of the album out of fear of litigation.

Zappa would go on to be a critic’s darling and all out innovator for the entirety of his career. His album Apostrophe would eventually be certified Gold by the Recording Industry Association of America for selling over 500,000 copies. His talent attracted some of the best session/touring musicians imaginable, including guitar phenom Steve Vai, drumming greats Vinnie Colaluta and Terry Bozzio, and singer Ike Willis.

An album like We’re Only in It for the Money is difficult for me to listen to because I revere Sgt. Pepper and don’t take kindly to Zappa’s satire when it’s pointed at an album I love. But, satire aside, We’re Only in It for the Money is creative playground that’s fun to listen to. It lacks the beauty of Sgt. Pepper, and, at times, sounds like a band of Gru’s minions, but no one can colorably call Zappa’s genius into question.

A