The crowdfunding campaign for the “Satellites” video has begun! Click on the video above to learn how you can contribute.

An Evening with Mike Garrigan

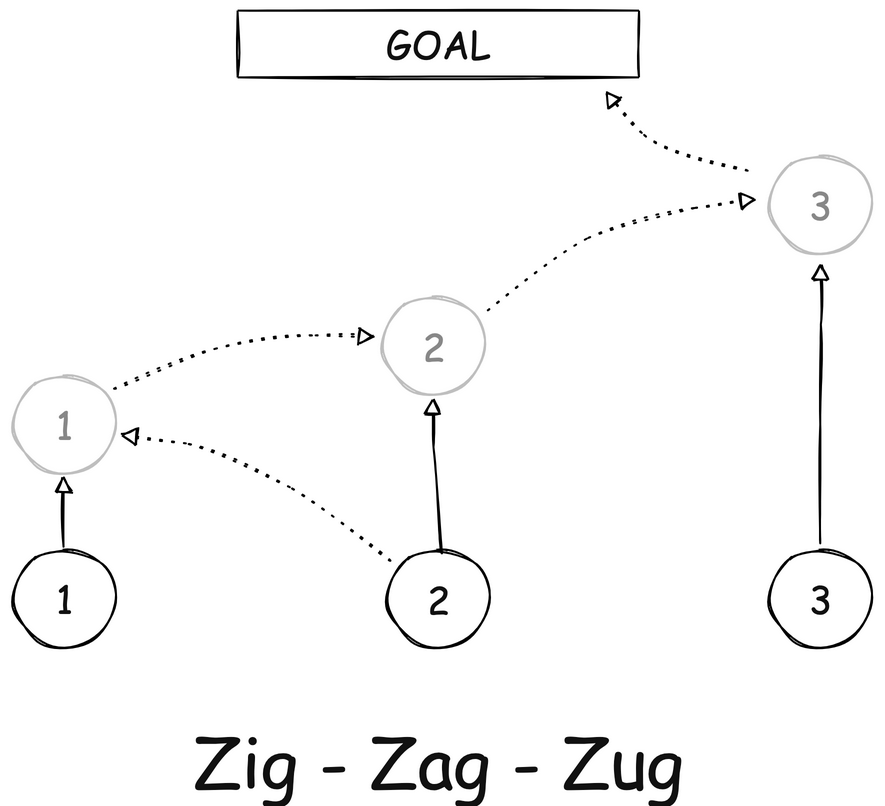

onPodcast: Zig-Zag-Zug – Confessions of a Little League Soccer Coach

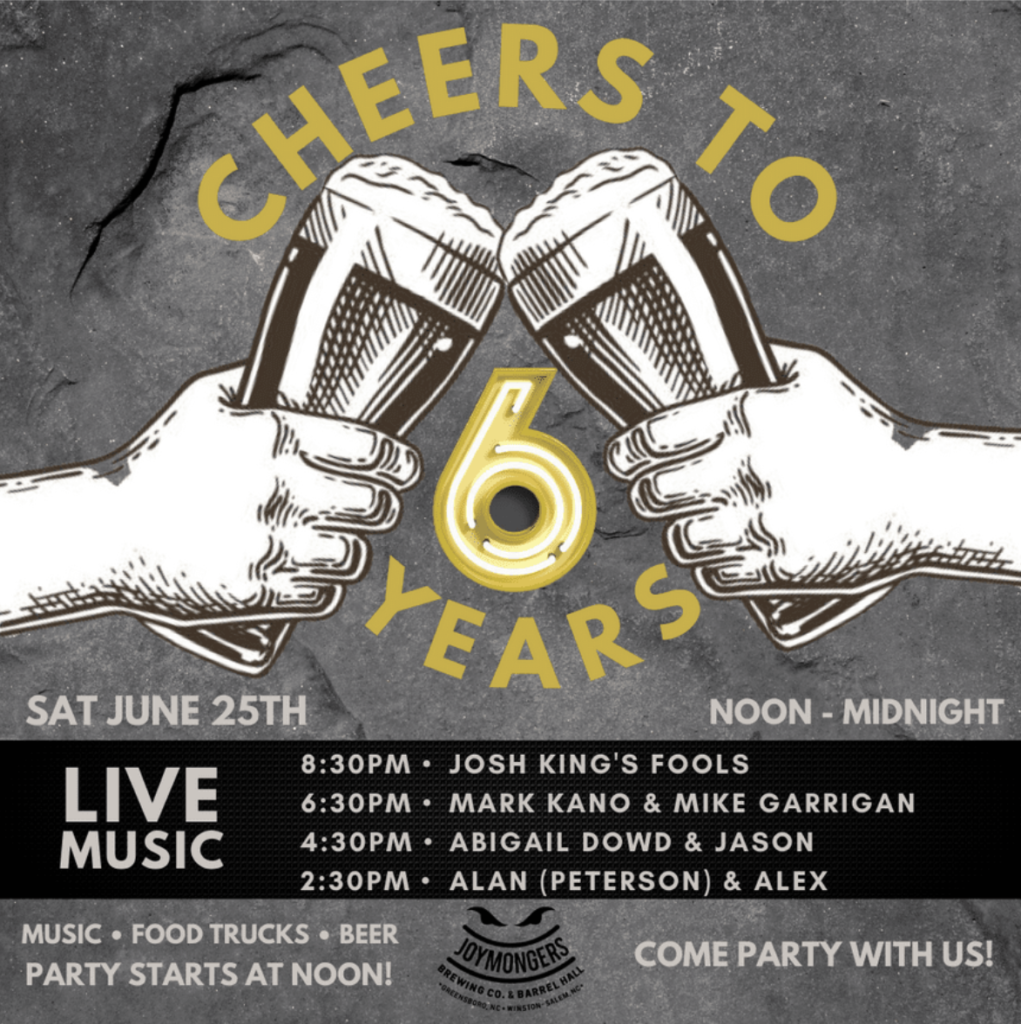

onMark Kano & Mike Garrigan @ Joymongers

on

Please join us on Saturday, June 25, 2022 at 6 pm at Joymongers, the Greensboro location. Find info here. Hear Athenaeum and Collapsis songs played with a full band as well as acoustic favorites.

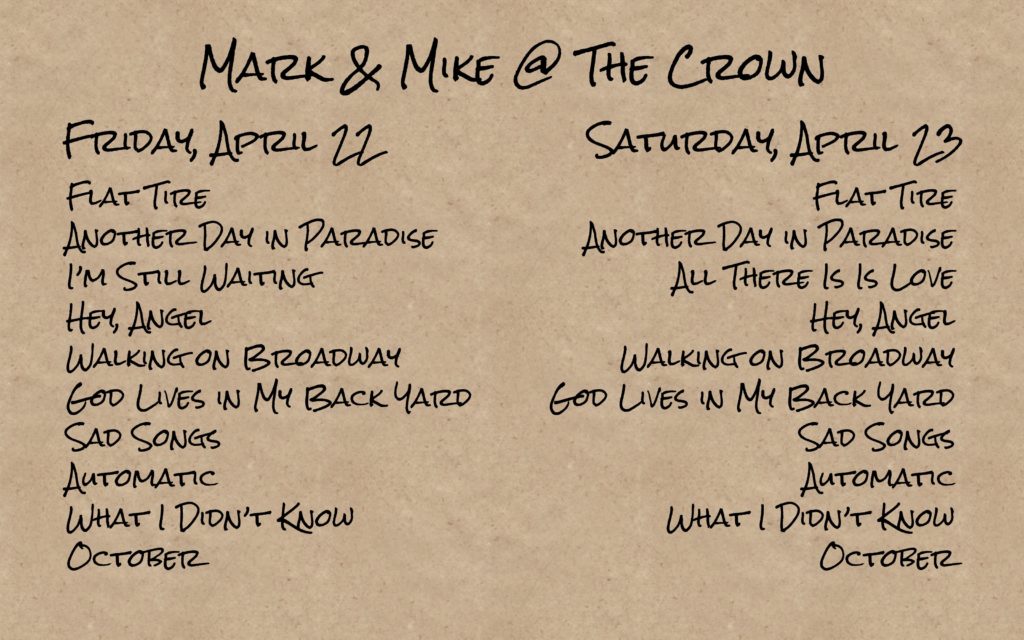

Show Reflection: Mike & Mark at the Crown

on

A few minutes after Mark and I finished our set on the second night of opening for Bus Stop at The Crown, Andy Ware walked in to the green room. I hadn’t seen Andy since December of 2019. Before the pandemic, we played a show at the Flat Iron. I began to laugh. Andy tells one of the best anecdotes about the Kiss concert at Dorton Arena back in 1976. I asked him if he would tell it again. It involves (1) a make-up malfunction where a mutual friend used his mom’s exfoliant as a white base for his own kiss make up and sustained a chemical burn, (2) a burning afro, and (3) a dejected fan sitting on the curb while coming to terms with an audience stunt gone wrong. You’ll have to get Andy to tell it to you but, believe me, it’s really funny.

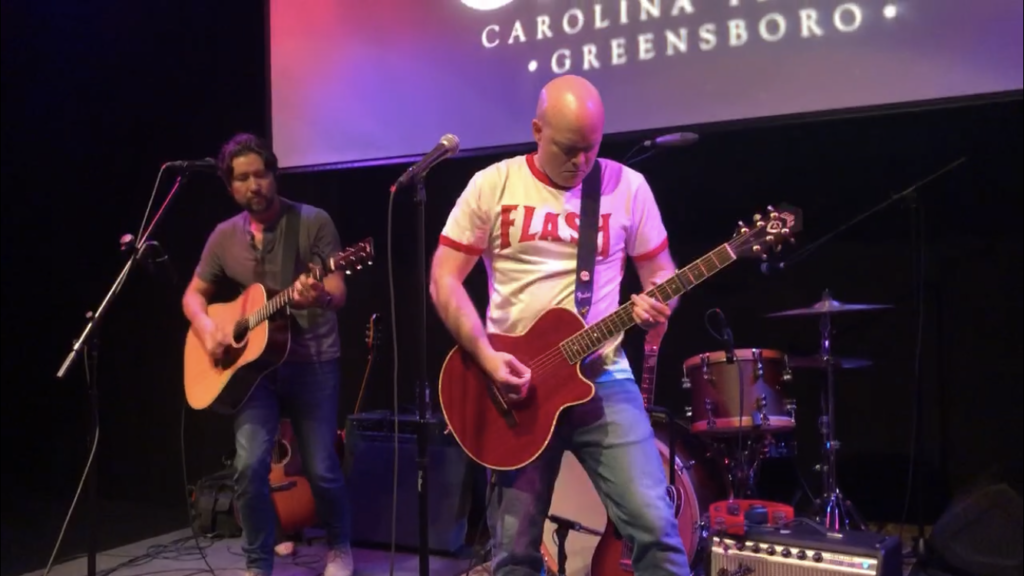

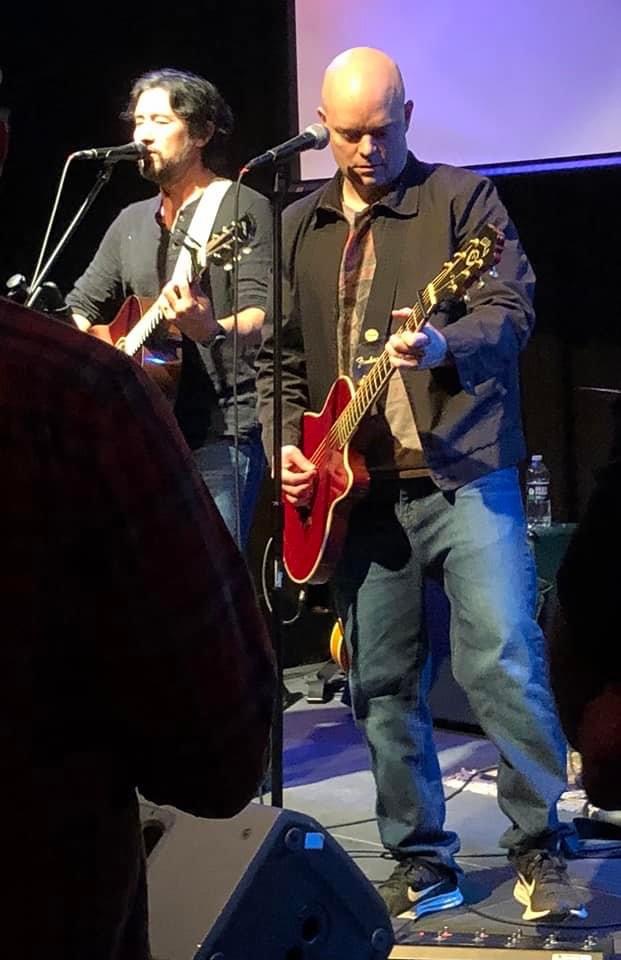

On Friday, April 22, 2022 and Saturday, April 23, 2022, Mark Kano and I played acoustic opening sets as part of the Bus Stop reunion at The Crown at the Carolina Theatre in Greensboro, NC. On both nights, we began at 8 pm and played for 45 minutes.

If, at the end of life, I get an official tally of all the shows Mark and I have played together, either as an acoustic duo or in one of several band settings, I wouldn’t be surprised if it were in the thousands. That being the case, we didn’t feel the need to rehearse for the show, but in light of the forced break from COVID and the high profile nature of these particular sets, we rehearsed the Wednesday before. We are professionals, after all.

Every show has obstacles. One obstacle was how the Crown is part of a larger complex of venues at the Carolina Theatre. On these particular nights, an unexpected costumed dance competition took place in the main theatre while we all congregated in the smaller room towards the top of the building. When we arrived on the first night, the entrance was locked and no one answered the “ring this bell” bell. We walked around to the front and were greeted by a finger shaking theatre official directing us to exactly where we had just been. She had a point. We really didn’t want to walk through a sea of tutu’s and angry dance moms, but sometimes you gotta ask yourself, “What choice do I have?”

A second obstacle was the venue’s interior design. Upon entering, I got the impression that the Crown was more of a black box theatre than a music venue. The sound system and monitoring was adequate, but the room wasn’t ideal for a 90s rock band playing at 90s rock volume and firing on all cylinders. Once people were in the room, though, everything was fine, but the soundcheck sounded boomy for everyone.

Our set on the first night had better energy. I usually wear earplugs as a matter of course. This first night, I thought, “Well, it’s acoustic and it won’t be that loud.” I was wrong. My monitor on the first song rattled my brain. After asking for an adjustment, things were better, but this first set felt more like walking a tightrope than playing a gig. My children were also in attendance and I was a bit nervous about sucking. You don’t wan’t your kids to think you suck. They liked it.

Our set on the second night sounded better. Of late, I use a Line 6 Firehawk amp for my guitar tone, whether playing acoustic or electric. Having tried miking the amp and using its direct out, I’ve concluded that the line out is the better audio feed. The Firehawk is more of a monitor with an amp emulator than an amp. Running the signal direct from the Firehawk cleared up the lower midrange on my end and helped everything mesh better. I didn’t have on my Freddie Mercury shirt, though.

The headliners played an impeccable set each night. Bus Stop had quite an influence on Athenaeum songs like “Banana” and Mark solo songs like “Sad Songs.” They have a knack for quirk, power, and musicianship–all in one fun show. Evan is still one of the best front men out there. Snuzz’s laid back style complements Evan’s energy. Chuck and Eddie hold down solid rhythms that sometimes morph from straight ahead rock, to reggae, to funk, all in the same song. It was an honor to be included in their 30th anniversary celebration.

I’ll get to hear Andy tell the Kiss story again in May when we rehearse for our full band set at Joymongers. Stay tuned.

Community Release – Common Grounds – Early Set

on

A live recording of the early set from my January 22, 2022 piano/vocal show at Common Grounds is now available in the Community. The set list was all of the Collapsis album, Dirty Wake, save one song.

- Automatic

- Tell Me Everything

- Believe in You

- October

- Superhero

- Wonderland

- Two Egrets

- Stumble

- Radio Friendly Girlfriend

- Dirty Wake

- Pure Triangles

StageIt – Cities

onAnchors

onPodcast: Story & Song, Vol 3

onShort Story: The New Parliament

onI’ve posted a short story called The New Parliament on Vocal. Enjoy. It’s about an owl named Felix.