Neither the ice storm nor the pandemic caused my show at Common Grounds to be postponed. On Saturday, January 22, 2022, from 8 pm until about 11 pm, I performed my first all-piano coffeeshop show.

Playing a piano show out live is uncharted territory for me. I’ve played solo piano limitedly, a few times, and I have been trying new gear setups each time. These have consisted of either running straight out through the stereo output of my Yamaha keyboard or using a less than ideal MIDI keyboard to trigger robust samples. This time, however, I tried using my Yamaha keyboard into my MacBook Pro where I triggered a piano in GarageBand. I liked this outcome.

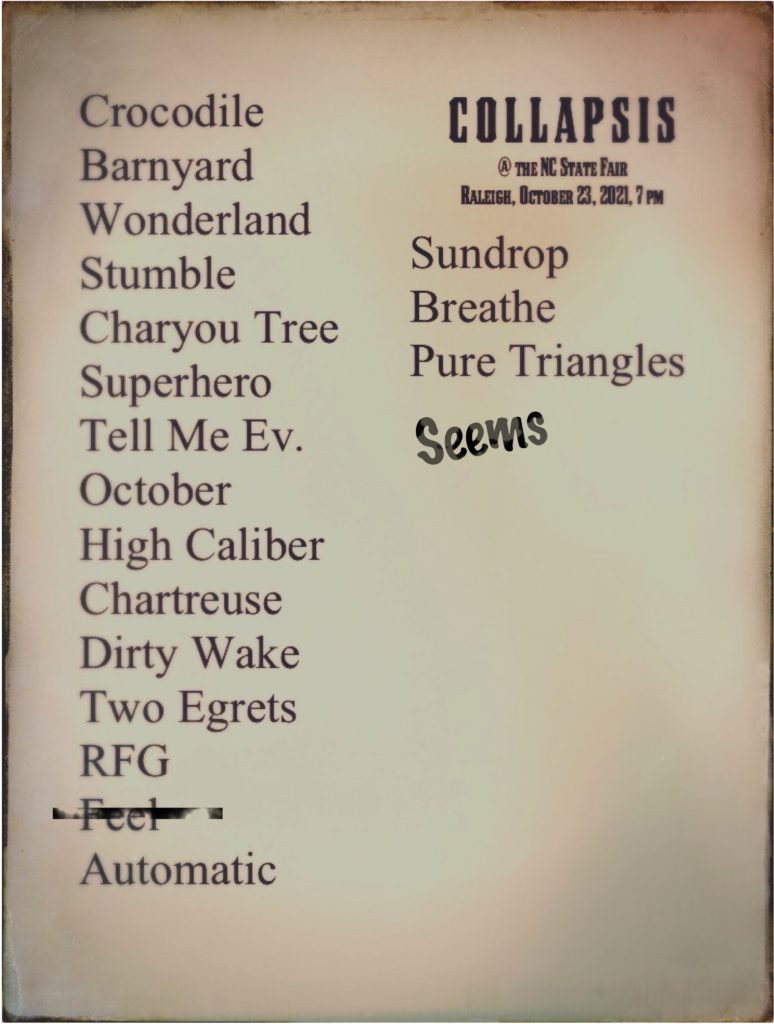

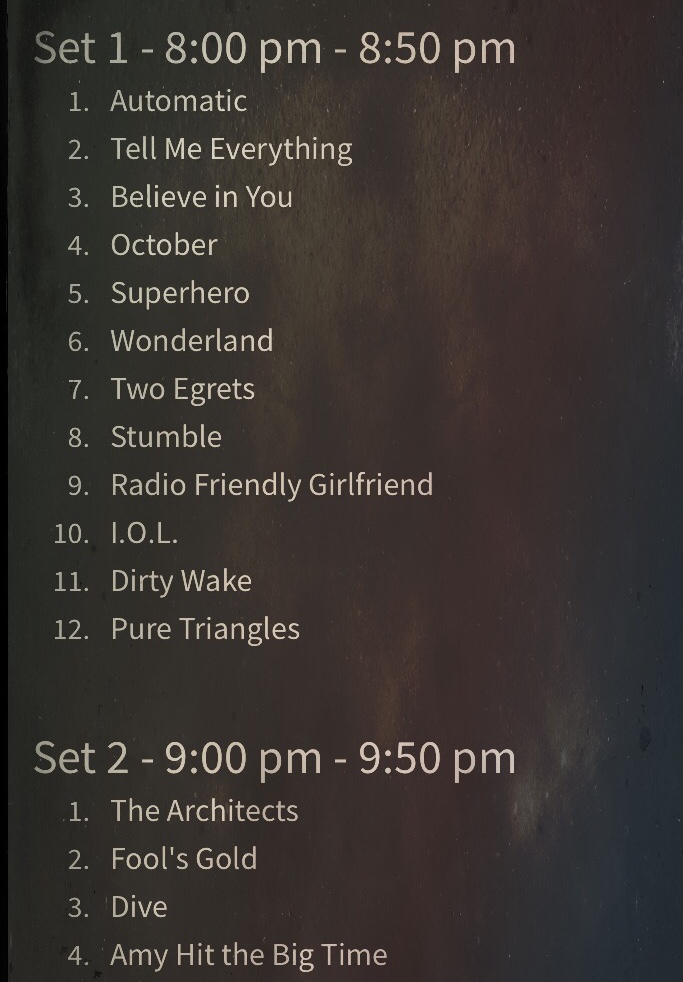

Collapsis played three reunion shows in 2021. As such, Dirty Wake, our principal album, has been on the fore-front of my mind. The first set of the evening was nearly all of Dirty Wake in sequence, with the exception of “I.O.L.” That song is tricky and seldom played. The second set was nearly all of Semigloss Albatross, the exception being “The Wall of Flies.” Rather than take a set break, I went straight into what was going to be the third set, which ended up being a handful of cover songs and balanced with a smattering of originals.

I look forward to doing this again. While my sets were structured, not all of the songs I chose lent themselves easily to the piano. Next time, a better approach would be two 45 to 50 minute sets, with more attention to overall flow and ease of performance.