For an album that only sold 30,000 copies during the year it was released, The Velvet Underground & Nico is a bit of an anomaly as influential albums go. When it debuted, The Velvet Underground & Nico was arguably too edgy to garner any airplay. But, as Brian Eno once said, “everyone who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band.” In a way, Eno’s observation explains why so many aspects of indie rock can be traced to this very album. From the overused glockenspiel accompaniment heard in contemporary commercials (first heard on “Sunday Morning”) to the use background drones (heard all over the album in the form of John Cale’s viola), all that indie rock would ever become is contained in this single album.

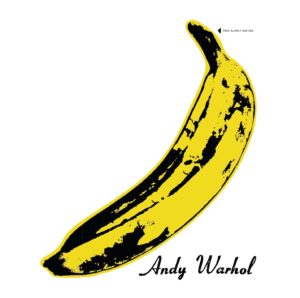

Released on March 12, 1967 and produced by Andy Warhol and Tom Wilson, The Velvet Underground & Nico is one of the first commercial albums to prominently feature graphic and overt references to drug abuse, sadism & masochism, and prostitution. Lyricist and singer Lou Reed was heavily influenced by edgy poets like William S. Buroughs and Raymond Chandler. In this respect, Andy Warhol’s contribution—as the person who paid for the recording sessions—was key. What record label would touch the Velvet Underground with a 10-foot pole? The music was edgy, too. John Cale’s strung his signature viola with guitar and mandolin strings for that never before heard death drone that appears throughout the album.

The Velvet Underground & Nico sounds oddly modern for an album released in 1967. As the Beatles recorded Revolver and Sgt. Pepper with an at-the-time cutting edge 4 track tape machine, The Velvet Underground & Nico likely could not have been recorded with more than 4 tracks. Some studios were transitioning to 8 and 16 track systems in the late 60s, but the low recording cost ($3,000.00) leads me to believe the less-track option was used. Somewhere, a book of some kind reveals this mystery, but I haven’t found the information readily available on the internet.

If you were to trace back the bare bones approach of Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago to its source, you’d end up at The Velvet Underground & Nico. The same can be said for just about any indie rock, lo-fi, or art rock recording. The album plays like the antithesis of convention, a giant, well-formed middle finger. The drums aren’t really played as much as hit now and again. The guitars carry much of the rhythm, which is strange because the album grooves well for having no acertainable rhythm section.

I’m embarrased that the first time I heard this album was just a few weeks ago. Lou Reed’s compositions are sharp, poignant, and challenging. Nico’s presence, which was at the insistance of Andy Warhol, is a divisive element in the Velvet Underground canon, but I rather like the tambre she brings to the three songs on which she sings lead. Few albums are both perfect and groundbreaking—this is one of them.

A